Could the Oilers be a team of destiny?

April 11, 2023

The time is now for Oilers’ Stanley Cup run

April 17, 2023Can the Edmonton Oilers take the next step? Lessons from the dynasty years, Part Two

EDMONTON, AB - MARCH 16: Edmonton Oilers Center Connor McDavid (97) celebrates his goal and 131st point in the third period of the Edmonton Oilers game versus the Dallas Stars on March 16, 2023 at Rogers Place in Edmonton, AB. (Photo by Curtis Comeau/Icon Sportswire)

April 17, 2023 by Bruce McCurdy

Over the 50 active seasons the Edmonton Oilers have entertained big-league hockey fans in this town – seven in the World Hockey Association, 43 in the National Hockey League, one (uncounted) in the deep freeze of a season-long lockout – there have been exactly two times a better future was obvious right from the start of training camp.

1979

The first was the seminal camp in the fall of 1979, Edmonton’s first in the NHL. A new course was baked in as a result of the merger of the rival leagues. While there was plenty of buzz about the famous visiting clubs we would be seeing in the season/s to come, most of the focus naturally fell on the home club. And there was plenty to be excited about.

The focal point was teenaged phenom Wayne Gretzky, already a known factor who had won the Lou Kaplan Trophy as the WHA’s last rookie of the year, finishing third in scoring in the Rebel League while leading the Oilers to first place. This from a willowy youth who was just 17 for the first half of the season. While many of the old school saw him as too slight to last in the big leagues, others saw the wunderkind as the future of hockey.

Another object of attention at that camp was the Oilers first-ever NHL draft pick. By terms of the merger the Oilers had been consigned to pick last in the Entry Draft, despite their official status as an “expansion” team. But in one of the deepest draft classes of all time, the Oilers chose wisely at No. 21 in selecting Kevin Lowe. He would go on to become a franchise cornerstone in a number of roles, not to mention Gretzky’s roommate in those early years.

The third was a very pleasant surprise. When Gretzky was sold to Edmonton in November of 1978, he was replaced on the Indianapolis Racers roster by Mark Messier, another 17-year-old hotshot straight out of St. Albert Saints of the Alberta Junior Hockey League. Messier scored just one goal in 47 WHA games with Indy and Cincinnati, but left an impression on Glen Sather when he “beat the snot out of Dennis Sobchuk”, then of the Oilers.

By virtue of his pro experience, Messier was made eligible for the NHL Draft, by some months its youngest eligible player. He somehow lasted until pick No. 48 when the Oilers snagged him. Expectations were all over the map, but from Day One of camp Messier – just eight days older than Gretzky – impressed with his exuberance, terrific speed, and soft hands. They would be the two youngest NHLers that season… though not rookies.

I wrote a retrospective of that camp some 30 years later, devoting a paragraph to each of the three standouts who would soon emerge as the core leadership group of the dynasty Oilers. By 2009, of course, the full arc of their fabulous careers was known, even as Lowe’s ultimate selection to the Hockey Hall of Fame was still more than a decade away. But what was entirely unforeseeable was how a future training camp just six years in the future would strongly resemble the “one-of-a-kind” that was 1979.

2015

In 2015, another trio of promising youngsters would stand head-and-shoulders above the crowd at rookie camp, and continue to draw rave reviews even after the veterans joined the scene. There was 18-year-old Connor McDavid in the role of wunderkind, 19-year-old Leon Draisaitl as the über -talented power centre in the mould of Messier, and 20-year-old Darnell Nurse who was already being projected as a bedrock defenceman in the fashion of Lowe.

The Oilers weren’t a brand-new team in 2015, indeed they were no strangers to having the pick of the litter at the NHL Draft. With first-overall selections Taylor Hall, Ryan Nugent-Hopkins, and Nail Yakupov already on hand along with another first-round gem in Jordan Eberle and coveted free-agent rearguard Justin Schultz, the likelihood of a dominant offensive team seemed imminent. But among those talented young pros, the still-younger trio of McDavid, Draisaitl and Nurse stood out as the squad’s emerging new core.

Eight seasons later that core remains, though the supporting cast around them has almost entirely changed. Hall, Yakupov and Schultz were all gone within a year, Eberle within two. Only Nugent-Hopkins remains as an éminence grise from the second rebuild, having seamlessly evolved into the ultimate team-first complementary player of the third.

Thus, the group of talented young players who attended that 2015 camp quickly shriveled to the 97-25-29-93 cluster, who today make up the core leadership group of the squad.

Moreover, future prized draft picks didn’t work out quite as hoped. Jesse Puljujarvi is a good hockey player but he’s no Jari Kurri. Kailer Yamamoto is a good hockey player but he’s no Glenn Anderson. Evan Bouchard is a good hockey player but he’s no Paul Coffey.

Only in the last couple of years have the Oilers finally built up a top-notch crew of complementary wingers, with the acquisition of free agents Zach Hyman and Evander Kane along with the (nearly) full-time conversion of RNH to the left flank. It took too long by half, but the 32-team NHL of the Salary Cap/Parity Era proved a much tougher nut to crack than was the high-scoring league of the post-expansion era.

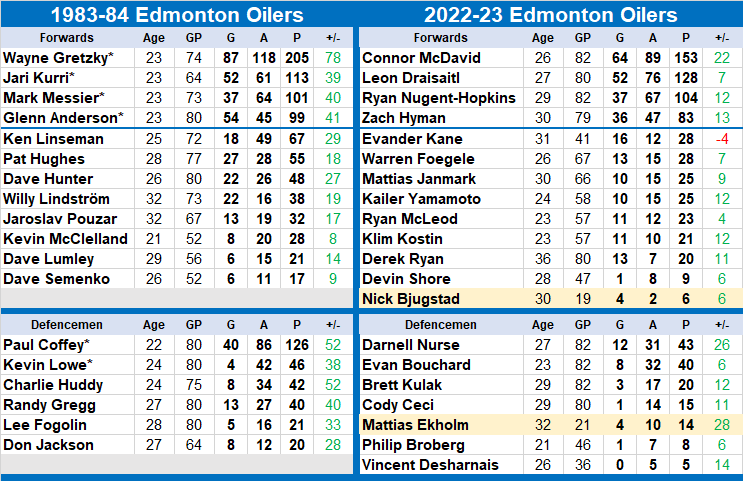

But, guess what? Scoring is finally on the rise, and once again it is the Edmonton Oilers who are leading the charge. Their 325 tallies in 2022-23 led the NHL by a tidy 24 (real) goals. While that’s nowhere near the stunning 86 tallies by which the 1983-84 Oilers led their nearest competitor, it is nonetheless substantial.

The modern Oilers have silenced all but the most foolish of critics of “one man team” criticisms, not that it was ever on point. (There were always at least TWO!) But as the 2022-23 season came to a close, the Oilers iced a group of 12 forwards who each scored at least 10 goals. That’s serious scoring depth.

Management

As his team has readied for a serious run for the Stanley Cup, current Edmonton GM Ken Holland has been a much busier man on the player acquisition front this season than was his distant predecessor. In 1983-84, Glen Sather brought in just a single outsider, Kevin McClelland, to tweak the ranks. For his part, Holland changed out at least seven, arguably eight positions in the past twelve months.

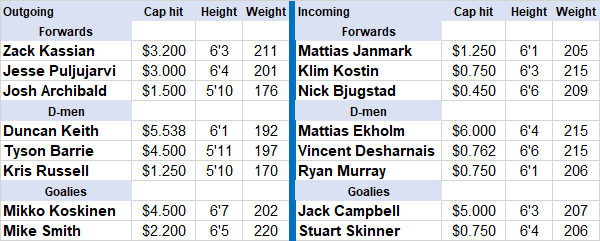

Of the eight newcomers, three came as free agents, three via the trade route, and two as internal promotions from the farm system. With the exception of Barrie-plus-plus for Ekholm, the exchanges were indirect, with players cleared out and then replaced in separate transactions. With so little correlation, players are simply listed in order of cap hit at each position.

A major objective of Holland was to trim some cap space in order to pay for substantial in-house raises for Nurse, Kane, Yamamoto and Brett Kulak, whose extensions all took effect in 2022-23 and had a collective cap increase of just over $10 million. Not something Glen Sather had to worry about in 1983, when his entire payroll was considerably less than $10 million and the salary cap was 20 years into a dystopian future.

But for Holland, cap compliance was a huge challenge. He accomplished it by replacing eight players costing $25.7 million with eight others costing $15.7 million (after retention). Hey, lookit! $10 million saved. It cost him significant assets on both acquisition side (Ekholm, Bjugstad) and disposition (Kassian), but the on-ice impact has been tangible.

The other thing Holland targeted was size. Let’s leave the goalies aside – all four of them are huge, and none, save Mike Smith on a feisty day, throw body checks let alone fists. The six skaters who departed averaged 6-foot and a half, 191-pounds; the sextet who replaced them, 6-foot-3 and a half, 211-pounds. Three inches and 20 pounds per man, among them enough to raise the team average by a full inch and about six pounds. In the process the Oilers have become a physically imposing club who can dish it out with the best of them. That’s one thing they have in common with that great Oilers squad of 1984.

Not all the changes have worked: Campbell, the would-be starting goalie, had a very erratic regular season, leaving the door open for the in-house promotion, Skinner. And depth defender Murray has spent much more time on injured reserve than he did on the ice, where he wasn’t effective in any event. The other additions have ranged from decent to very good, with Skinner, Desharnais and Ekholm proving to be revelations.

Coaching

How much of the credit is due on the coaching vs. management side is open to question. With the old Oilers, Sather took the credit (and the criticism) on both sides of the equation. For the modern club there is a clear division of labour. Make no mistake, though, head coach Jay Woodcroft and his staff have made their mark, and proved it in last year’s playoff run when the Oilers won more series than they had in the previous fifteen seasons combined.

Though constricted to a bare-bones 21-man roster in 2022-23, Woodcroft has continued to ice varied lineups that consist of either 11 forwards and seven defenders, or the more traditional 12 and six, both to good effect. One outcome is the Oilers are exceedingly difficult to match up against, especially given the nuclear weapons that occasionally show up on the “fourth line” in the 11 and seven deployment. It helps that a majority of Oilers forwards can play multiple positions, allowing the coach all sorts of options when matching lines, or countering same.

One change Woodcroft & Co. have stuck to for the most part this season is using Leon Draisaitl almost exclusively at the centre position, largely ignoring the temptation to pair him up with Connor McDavid, as has been done with devastating effect in the past. It’s helped that Edmonton has spent much more time leading than trailing games in the second half of the season.

The switch doesn’t quite have the finality of Messier’s move to centre in 1983-84; indeed, Woodcroft did similar last season before an ankle injury to Draisaitl in the playoffs forced the coach’s hand. With fabulous results, mind: McDavid and Draisaitl comfortably finished 1-2 in playoff scoring despite not making the Finals, each averaging two-plus points per game.

Another echo of the dynasty Oilers has involved the regular deployment of McDavid on the penalty kill, where he has excelled. No. 97 saw his ice time increase by a factor of six over last season, scoring 4-3-7 and generating a remarkable 47 percent goal share (8 for, 9 against). Teammates followed his lead on occasion, and the club as a whole produced 17 shorthanded goals to lead the NHL. Not quite the 36 shorties the Oil scored in that magical 1983-84 season, but a distant echo at least. Even in an outnumbered situation, world-class players can be a threat lining up against offensive-minded opponents; who knew? Old Oilers fans, that’s who!

One area where the modern Oilers are distinctly superior to their dynastic forebears is on the powerplay, which established a new NHL record for efficiency with a conversion rate of 32.4 percent. The last team to lead the NHL in both power-play and shorthanded goals in the same season? The 1980-81 Islanders.

Comparison

Let’s close with a direct comparison of the two clubs. We’ll use regular season results for the obvious reason the

’23 playoffs haven’t actually started yet:

I would argue this is the first time the Oilers have had a team good enough to make such a comparison, even as it will inevitably come up short against the greatest scoring club of all-time … not to mention one that played in a season that produced 24 percent more goals per game.

Both teams are/were led by the best player on the planet. Both feature/d a terrific top-four up front that is the envy of the league. The squad of the ’80s had more secondary scorers in the 20-goal range, while the modern group is a little deeper, at least on the goal production front. The largest difference by far is the absence of a Paul Coffey- type super scorer on the back end. Coffey aside, both teams had three defenders with 40-plus points; even when the Oil moved on from Barrie at the deadline, Ekholm came in and scored at a 55-point pace down the stretch.

The current squad has the better goaltending numbers, though that too is era-dependent. Much depends on Stuart Skinner, who just broke Fuhr’s 41-year-old record for wins by a rookie but is about to get his baptism by fire in the postseason.

While in most respects the modern Oilers fall a little short of their brilliant predecessors, in 2022-23 they enter the playoffs on a hotter end-of-season roll (14-0-1) than any of Edmonton’s five Stanley Cup champions did. Can they sustain it? Aye, laddie, that’s why they play the games… and why we watch them.